In a landmark case that might redefine race’s consideration in the electoral districting of the United States, the Supreme Court is considering whether the Constitution itself must be read as “colorblind”—even in attempts to redress racial discrimination by civil rights legislation.

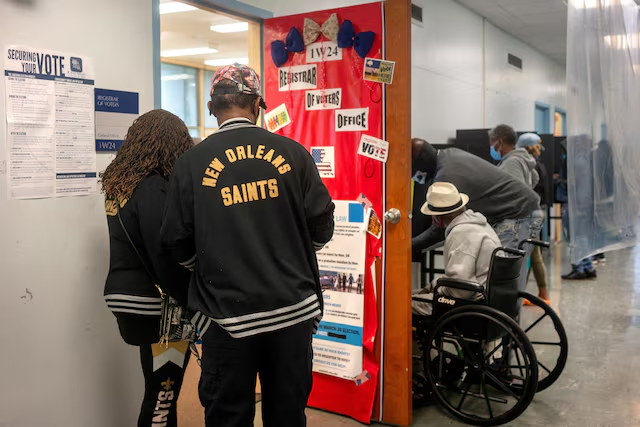

At its center is a redistricting proposal passed by Louisiana lawmakers following a ruling by a federal court that said the former congressional map likely violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) by diluting the voting power of Black citizens. The new map increased Black representation by adding a second majority-Black congressional district in a state where Black residents make up roughly one-third of the population.

But the new map has been disputed by a group of white voters who argue that the legislature unfairly concentrated on race when they redrew the lines—presumably ignoring constitutional protections.

A “Colorblind” Constitution?

Making his case for the plaintiffs, lawyer Edward Greim put before the Court the argument that while addressing long-standing discrimination may have once been a valid justification for using race-conscious remedies, those remedies were never intended to be long-term under what he called a “colorblind Constitution.”

“If ever legal under our colorblind Constitution, it was never intended to endure forever,” Greim had argued in oral arguments.

His contention is a broader conservative approach to constitutional law that the Constitution does forbid any government racial classification—no matter the context. It contends that all people must be treated equally under the law, and so the government must be equally colorblind.

But its critics argue this interpretation omits consideration of historic and ongoing racial disparities. Even most civil rights activists and legal scholars warn of a rigid devotion to so-called “colorblindness” potentially being a cover for policies that reinforce structural disparities.

The case offers the conservative majority of the Supreme Court the opportunity to build on its attempts to undo the Voting Rights Act, Section 2, which prohibits voting rules or district maps that cause minority voting power to be diluted even absent explicit racist intent.

Most justices, including Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, appeared skeptical of the current application of Section 2 throughout the hearing. Kavanaugh echoed the complexity of the case, saying, “The goal, of course, is racial nondiscrimination. But, at the same time, given history and Congress’s actions, the goal is making sure that there have been sufficient remedies for the history of discrimination in the United States.”

The Court’s weighing of the matter is only two years since its historic 2023 ruling marked the end of the weighing of race in admissions at the college level. In that instance, Roberts wrote: “Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.” That sentiment does not seem to be gaining traction in the redistricting debate either.

The Role of the Reconstruction Amendments

Greim and other opponents of the new map contend it violates the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution—governing Reconstruction-era amendments passed in the wake of the Civil War.

The 14th Amendment guarantees equal protection under the law.

The 15th Amendment prohibits voting discrimination based on race.

Together with the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, these provisions are landmark in civil rights law.

But some academics argue the very history of these amendments substantiates concerted action toward ensuring racial equality in democratic participation. UCLA constitutional law expert Richard Hasen called the prospect of applying these amendments to forestall safeguards for Black voters “ahistorical and repugnant.”

Remnants of the 2013 Shelby County Decision

Our case today dates back to the decades-long conservative effort to dismantle the Voting Rights Act. In 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, the Court invalidated Section 5, which required certain jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination to get federal permission before making any changes in voting procedures. That decision greatly weakened the federal government’s power to oversee election law in the South, including Louisiana.

Follows Section 2, the last large tool for reversing racially discriminatory voting laws. Legal commentators assume the Court would choose to reinterpret rather than entirely invalidate the provision.

“this Court could revisit the test used under Section 2, and make it more restrictive on when race-based remedies are permissible,” said Michael Dimino, a law professor at Widener University. “Short of declaring Section 2 unconstitutional, that would have massive impacts on voting rights cases.”

Sotomayor Pushes Back

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a liberal voice on the Court, strongly defended considering race during redistricting, considering its practical necessity in protecting minority representation.

“Race is part of redistricting—always,” she said. “And it can be used to help people.”.

She referred to a 2023 Alabama case in which a long-standing discriminatory map was successfully overturned. “That map was in force for nearly the entire life of the state. It was enacted because it was discriminatory—and it continues to have that effect,” Sotomayor warned.

DEI, Affirmative Action, and Broader Political Landscape

The case is also an example of a broader political movement—conservative and led by ex-President Donald Trump—to dismantling Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives across education, business, and government. Trump’s administration openly supported moving against civil rights protections that were “race-based.”

In the case, Trump supporters and Louisiana Republicans have signed up with the white plaintiffs who are pushing to invalidate the new map.

What’s at Stake?

A decision in this case would drastically curtail the recourse available to minority voters seeking equal representation—especially where racial gerrymandering has occurred in the past.

Janai Nelson, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, was counsel for Black voters and argued to the Court that race-conscious remedies are also constitutionally permissible when they are a response to established and targeted discrimination.

“By deciding the student admissions case, the Court explained that race could still be used so as to counter discrimination that has been recognized,” Nelson said. “That’s exactly what’s happening here in Louisiana.”

With the verdict expected to be issued by June 2025, legal analysts point to the Court possibly taking one of a number of paths: uphold the map, reinterpret Section 2 to limit remedies based on race, or go so far as to declare segments of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional.

Whichever its verdict, the ruling is likely to have wide-ranging implications for how American democracy struggles to make sense of race, voting rights, and representation in the coming years.