Almost six decades after the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965—a landmark law that swept away racial obstacles to the polls—the venerable legislation is confronts one of its gravest threats ever.

The threat this time is not from the White House or Congress but from the U.S. Supreme Court, whose 6–3 right-wing majority is poised to dilute yet another pillar of the Act.

A Legacy of the Civil Rights Era in Jeopardy

Enacted from the Civil Rights Movement and led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Voting Rights Act (VRA) was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson to prohibit discriminatory tactics like literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation that previously disenfranchised Black voters in the South.

The VRA’s purpose was simple but deep: to ensure all Americans, whether color ed or not, had an equal opportunity to reach the ballot box. But more recently, that promise has been hollowed out by court rulings and partisan redistricting battles.

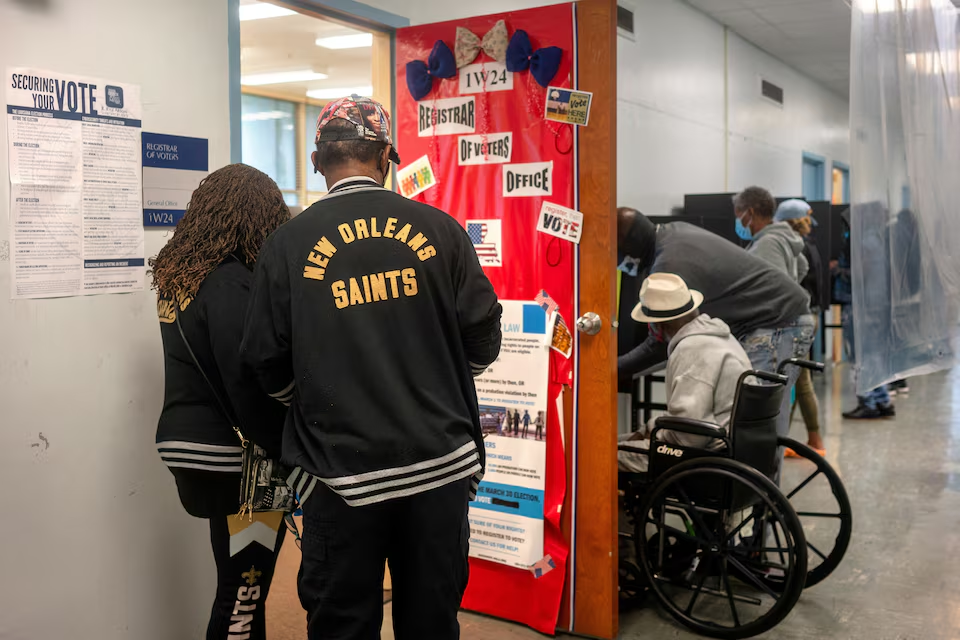

The Louisiana Case: A Flashpoint for Section 2

At the center of this day’s controversy is a Louisiana congressional map that specifies how the state’s six U.S. House districts are redrawn. Black residents comprise approximately one-third of Louisiana’s population, yet only one of its districts ever has had a majority of Black residents.

After a ruling by a lower court that the map watered down Black voting strength—violating Section 2 of the VRA—the Republican-controlled legislature reluctantly created a second black-majority district. A group of white voters, however, challenged the new map on the basis that it was racially gerrymandered and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

The case, before the Supreme Court this week, could revolutionize the courts’ conception of Section 2—a provision prohibiting electoral maps and voting rules that result in racial discrimination, even in the absence of evidence of intent.

What’s at Stake

If the Court dismantles Section 2, vote rights advocates say, states with a legacy of racial discrimination would be able to redraw maps that systematically disenfranchise minority voters.

“Further weakening Section 2 would allow states to make politics about staying in power and keeping Black, Latino, Native, and Asian American communities quiet,” said Sarah Brannon, deputy director of the ACLU Voting Rights Project.

Legal experts fear this would effectively “gut” Section 2—making lawsuits against discriminatory maps well-nigh impossible to win. “Courts may throw these cases out before they even reach the trial stage,” said George Washington University law professor Spencer Overton. “That would make legislatures immune to craft maps for the benefit of incumbents and disenfranchise voters of color.”

A Legal Tug-of-War Over Race and Representation

The Trump administration earlier joined the white voters in a lawsuit against the Louisiana map, contending that redistricting must not be dominated by considerations of race. Although short of a demand to repeal Section 2, Trump’s Justice Department introduced a revised framework that would place limits on “excessive consideration of race” when districts are drawn—prioritizing so-called “race-neutral” concepts like the preservation of incumbents.

Opponents, however, claim that this way of thinking ignores de facto overlap between politics and race in the real world. In the Deep South, for instance, more than 80% of Black voters voted for Democrats, so attempting to sort out racial bias from partisan reasons would be all but impossible.

“It would make it extremely difficult for minority voters to prove discrimination in redistricting,” claimed Travis Crum, a Washington University law professor in St. Louis.

A Court Continuously Sharpening Civil Rights

The legal landscape in the United States on issues pertaining to race has already been reshaped by the current Supreme Court. In 2013, the Court decided in Shelby County v. Holder and struck down a key element of the VRA requiring voting jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to seek federal approval before they could change voting rules.

Most recently, in 2023, the Court ended race-conscious admissions to colleges, and conservative lawmakers across the country—copying former President Trump—have sought to wipe out diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

“The Voting Rights Act was designed for a time when racial discrimination at the polls was blatant,” political analyst Dr. Elaine Porter said. “But today it’s about more insidious and institutionalized forms of disenfranchisement—and the Court is less willing to intervene.”

Justice Kavanaugh’s Pivotal Role

During oral arguments, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who is thought to be a possible swing vote, seemed sympathetic to the Justice Department’s suggestion, saying it might resolve the “concerns” regarding racial considerations in redistricting.

But Louisiana’s Republican solicitor general, Benjamin Aguinaga, pushed further, contending that Section 2 itself—when it mandates race-based redistricting—is unconstitutional.

This argument tracks with conservative assertions that the Constitution mandates “colorblindness,” a notion critics say overlooks the nation’s racial disparities.

“If the Court goes along with this view,” said Mark Meuser, an attorney for Republican candidates, “it will reduce costly lawsuits and put more onus on those claiming racial bias.”

But civil rights groups worry that this “colorblind” interpretation could erase decades of gains. In a report for Fair Fight Action and the Black Voters Matter Fund, the repeal of Section 2 protections would allow Republicans to redistrict up to 19 congressional seats nationwide—allegedly tipping the balance of power in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Despite the uncertainty, activists vow to continue the fight. “Regardless of the outcome, we’re going to continue fighting for equal representation and fair maps,” Brannon of the ACLU said.

The Supreme Court ruling, imminent in the coming few months, could reshape American democracy’s future—deciding not only political boundaries, but also who has a voice within them.

Background: What Is Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

Section 2 prohibits racial, color, or minority language group-based discriminatory voting practices.

It was broadened in 1982 with a “results test,” meaning plaintiffs no longer have to prove intent—only that a law had a discriminatory effect.

The standards established by the Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) ruling have been tested by recent cases.

The Bottom Line

The Voting Rights Act has stood for decades as a bulwark against diluting American democracy. But as the Supreme Court revisits its roots, the question looms larger than ever: Will the right to vote remain equally protected for all Americans—or just for those whose already are loud and clear on the nation’s political landscape?