Like many postpartum mothers, 33-year-old Liz (who did not want her last name published) struggled to feel comfortable in her own skin after giving birth. Postpartum weight gain had her seeking answers, and even though she looked into prescription weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic, the cost placed them well out of her range. Online pharmacies’ compounded forms gave her some relief, but even those were not in her budget.

It was there that Liz learned of a new, controversial trend: “gray GLP-1s.” They were made famous on TikTok and websites online, where “gray” referred to people who were getting research-grade peptides and mixing them into homemade replicas of GLP-1-like medications in home kitchens. What was at first presented as a cost-saving shortcut soon developed a darker, more sinister undertone to America’s obsession with weight-loss medication.

“I started in the spring,” said Liz of her home experiment. Paying about $100 for 10 months’ worth of medication seemed a reasonable trade-off to the $300–$400 per month price tag of name-brand drugs. She dropped 30 pounds and says she feels like herself again, but she admits the risks: “I know it isn’t safe. But the system doesn’t give people like me affordable options.”

What Are “Gray GLP-1s”?

GLP-1 medications such as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro have skyrocketed in popularity the last few years, being prescribed for diabetes as well as immediate weight loss. With more demand than supply, prices skyrocketing, an open black market has appeared.

So-called “gray GLP-1s” are peptides labeled “research use only” purchased online from suppliers. Their users like Liz reconstitute or dilute the powders into injectable form, often according to hints in TikTok videos or encrypted messaging groups and not from physicians.

The phenomenon scares doctors, pharmacists, and regulators. “These are black market drugs, period,” says Courtney Sullivan, a pharmaceutical regulation expert in Arizona. “There’s no FDA oversight, no quality controls, and no way to ensure what’s really in those vials. Referring to it as ‘gray’ is minimizing the danger.”

Why People Turn to the Gray Market

Despite risks, Americans are willing to gamble on off-label drugs. The why is clear:

Affordability: FDA-approved GLP-1s are $1,000 or more per month without coverage. Even compounded products from licensed pharmacies are hundreds of dollars.

Insurance Barriers: Only diabetes patients are covered, not those who are treated for obesity without diabetes.

Access Issues: Shortages and delayed supplies have left many patients without prescription access.

It’s a desperate measure,” says Sabina Hemmi, co-founder of GLP Winner, an activist organization that keeps track of the weight-loss medication market. “People see others online losing weight quickly, they encounter problems with the healthcare system, and suddenly the black market appears to be the only solution.”

Medical and Legal Concerns

Doctors warn that “gray” products can be unsafe or even life-threatening. Others have no active ingredients at all, and others have unidentified contaminants.

“I have patients who have lost well over 100 pounds with legitimate GLP-1s, and they say it’s changed their lives,” says Lindsey Landers, an APN in Kentucky. “But when they lose access, some try to go underground and get it from illegal online sources. It’s devastating because these patients are desperate.”

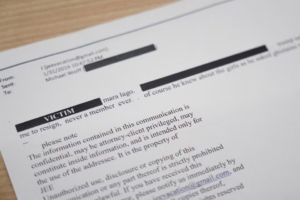

Landers indicates that she began to discontinue prescribing compounded GLP-1s from a licensed pharmacy after she received an August 2025 cease-and-desist letter from a pharmaceutical company. Her less affluent patients have had no option but to make an impossible choice because: shell out thousands of dollars out of pocket for name-brand medication, or risk their health with “gray” alternatives.

The TikTok Effect and Parasocial Guidance

Social media also fueled the boom in “gray GLP-1s.” TikTokers and influencers are filming themselves mixing powders in their home kitchens, promoting stupendous weight-loss results. Many of these appear presented as educational, but experts say that gives them a pseudoscientific sheen.

“Research-use only means the peptides are not for human use,” Sullivan explains. “But sellers market them in ways that erase the difference, and social media helps spread the illusion that this is some kind of do-it-yourself health hack.”

Mysterious chat rooms now act as shadow communities, offering dosing instructions, product ratings, and vendor recommendations. They’re often paid for with cryptocurrency in order to remain untraceable.

The Bigger Picture: Why “Gray” Won’t Disappear Soon

Experts argue that the “gray” market exists as a consequence of the healthcare system failing to provide weight-loss medication at an affordable and accessible rate for all. As long as costs remain high and demand continues to rise, people will find themselves continuing to seek cheaper, riskier options.

“Vanity weight loss is not what this is about,” Hemmi stresses. “For some patients, GLP-1s are a lifeline for managing obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. But if access is limited, the black market kicks in.”

Liz agrees, although she admits to knowing the risks. “I wish there was a cheaper, regulated alternative,” she says. “People like me wouldn’t have to do this if the system actually gave us safe, affordable options.”

Final Takeaway

The development of “gray GLP-1s” shows where medical innovation, social media influence, and the cost crisis of US health care intersect. Regulators tell consumers for the moment to avoid these illegal drugs, but until systemic reform comes along, many patients will continue to sacrifice safety for results.

As Sullivan states: “The only way to protect patients is to provide effective, safe medicines. Until then, individuals will keep putting their health at risk.”